Harm Reduction and the Struggle for Survival in Arkansas

- Rahem White

- Sep 17, 2025

- 3 min read

To speak about harm reduction in Arkansas is to speak about survival. It is to confront the plain fact that there are people in this state who use drugs, who share needles, who engage in sex work, who are shamed for doing so, and who will live or die depending on whether they have access to basic tools to keep themselves safe. This is not theory or conjecture. It is flesh-and-blood reality.

Arkansas ranks first in the nation for the increase in new HIV cases. Approximately four hundred people were diagnosed with HIV in 2022. At the same time, hundreds of Arkansans died from overdoses, most of them involving fentanyl. The numbers are not abstract. Each one is someone’s child, someone’s sibling, someone who should still be here were it not for the strict prohibitionist policies that have failed them.

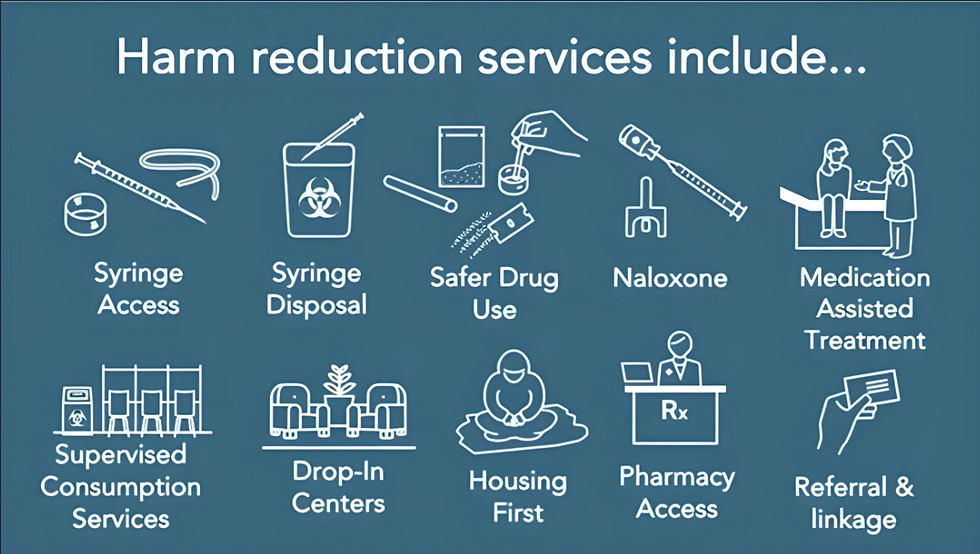

The logic of harm reduction is simple: if you provide people with clean syringes, they are less likely to share them. If you make naloxone widely available, more overdoses are reversed. If you make condoms and HIV testing easy to get, fewer people will contract the virus. There is nothing complicated about this. It is neither charity nor leniency. It is the recognition of human dignity in a space where that dignity is often denied. Arkansas has only three syringe service programs. For a state of more than three million people, this is not enough. Rural communities are left without options. People who use drugs in small towns must drive long distances or risk arrest. Too often, they choose to stay hidden. And hidden epidemics spread.

The barriers are not only physical but moral. Policies in this state still treat harm reduction as suspect, as if providing someone with a sterile syringe is an invitation to ruin, as if saving a life from overdose is a political statement. The stigma is thick. It keeps people from seeking care. It keeps organizations small and underfunded. And yet, harm reduction persists. Volunteers pack kits with syringes and fentanyl test strips. Outreach workers walk under bridges and into encampments with naloxone and a word of respect. They remind people that they are not disposable. They remind the rest of us of what being in community with one another truly means.

If we are serious about ending HIV in Arkansas, we must be serious about harm reduction. We must invest in more programs, change the laws that punish survival, and speak against the shame that has cost too many lives. Harm reduction is not only a public health strategy. It is an act of witnessing — of saying that even here, even now, in a state where HIV is rising faster than anywhere else, every life is worth saving.

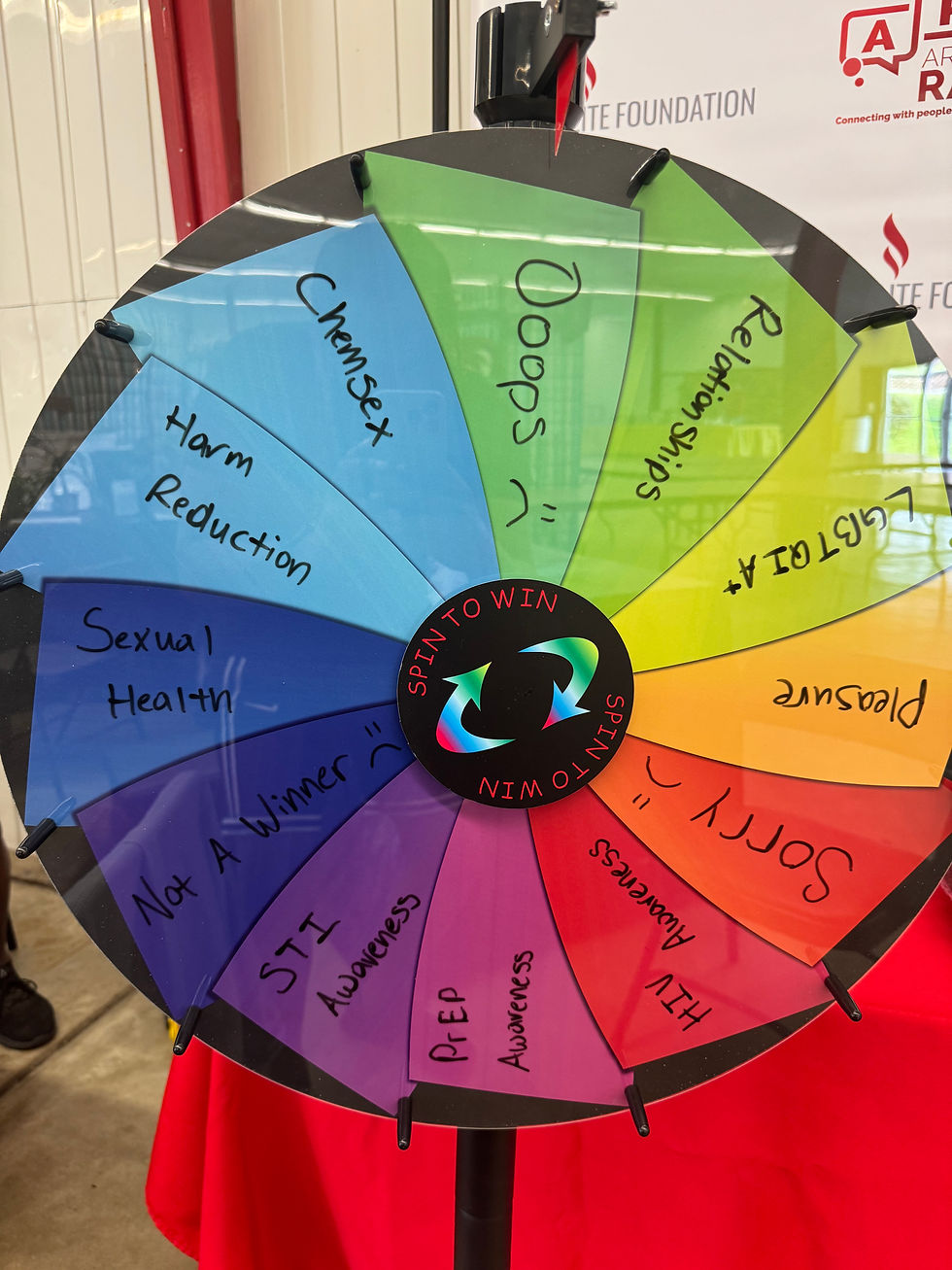

I challenge you to bring harm reduction into someone's awareness today. Talk about why it matters. Share the facts about HIV, overdose, and survival. Each conversation chips away at stigma. Each person you reach may reach someone else. This is how harm reduction grows; not only through programs and funding, but through you carrying these ideas into every space you touch.

.jpg)

Comments